Making Overtures: Programmatic vs Absolute Music, Part 2

In our first edition of Making Overtures, we discussed a distinction between programmatic music and absolute music:

Generally, in programmatic music, a composer portrays a definite picture of events or objects, or even an entire story. You may hear a representation of a thunderstorm, a braying donkey, a clock striking 12, or Juliet’s beating heart.

On the other hand, in absolute music, the composer offers us pure music for its own sake. We relate to its rise and fall, tension and relaxation in a more visceral way, without having to associate it with prescribed imagery.

https://isomusicians.org/2021/07/making-overtures-programmatic-vs-absolute-music/

Our classical series programs Greetings from Italy (February 17-19) and Greetings from Germany (February 25 and 26) offer a juxtaposition of these two ideas. The program of Greetings from Italy features a few pieces of a programmatic nature:

Overture to Il barbiere di Siviglia, Gioachino Rossini

Symphony No. 4 “Italian”, Felix Mendelssohn

Harold in Italy, Hector Berlioz

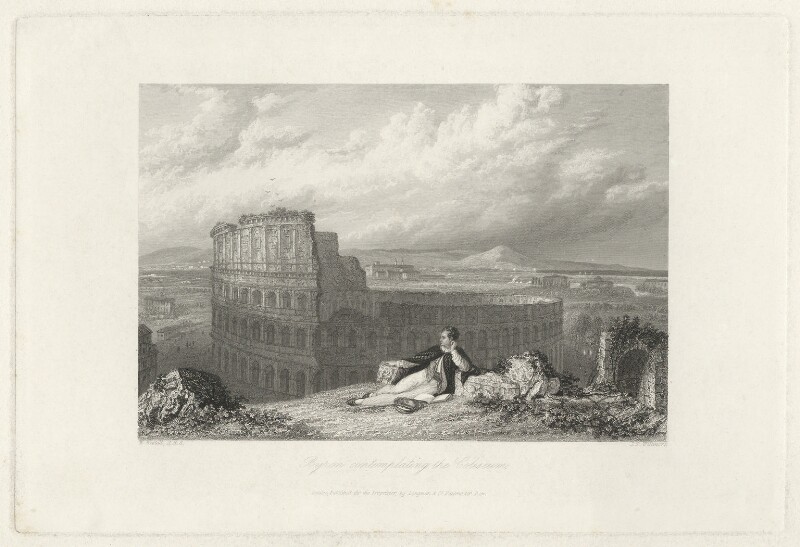

The final piece is most notable, as Hector Berlioz (1803−1869) believed that music could describe or express something beyond itself; for instance, a story, a landscape, or a particular mood or feeling. He was a radical innovator in how he employed the forces of the orchestra to express himself, greatly expanding the number and type of instruments used in the classical era orchestra to achieve the colors and moods he wished to represent. Harold in Italy depicts a series of scenes inspired by Lord Byron’s poem Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, describing Harold’s melancholic travels in the mountains, an encounter with pilgrims, a love serenade for his mistress, and finally a scene among a group of brigands.

In contrast, the program for Greetings from Germany consists of pieces in the nature of absolute music:

Brahmsliebewalzer (3 waltzes for orchestra), Wolfgang Rihm

Cello Concerto No. 2, Op. 30, Victor Herbert

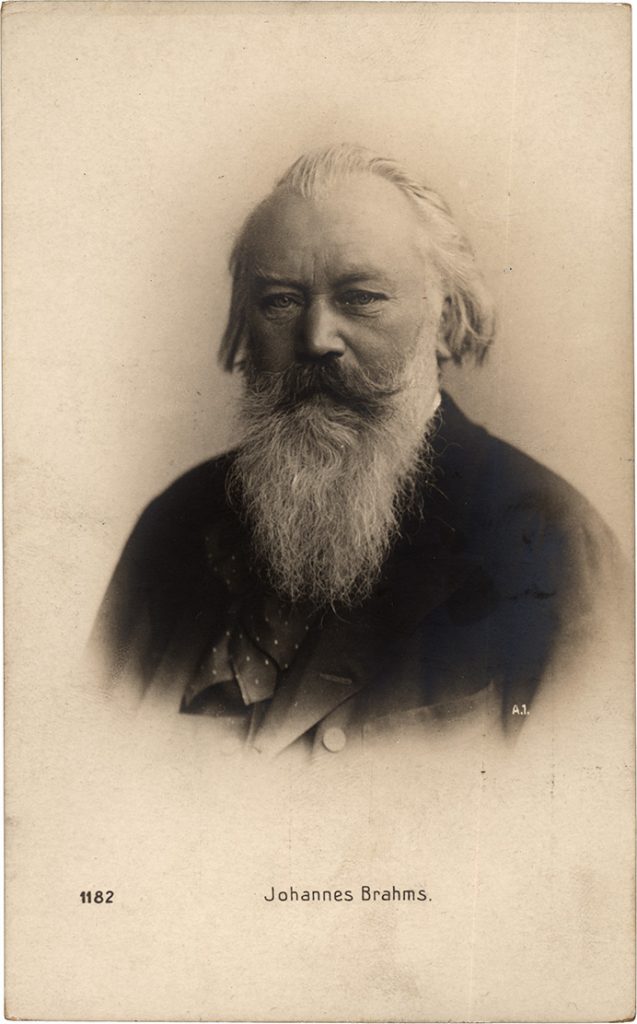

Symphony No. 4, Op. 98, Johannes Brahms

To quote musicologist and symphonic trombonist William E. Runyan:

[Johannes Brahms (1833 – 1897)] most significantly, still adhered strongly to the style of Beethoven that focused on the purely musical. He and other conservatively minded musicians held that the traditional forms of sonata, concerto, and symphony had not nearly exhausted their viability, and that music should continue to speak in an integrated language that referred to itself, alone, and certainly not to extra-musical ideas. So, he and his ilk continued to write “pure,” or “abstract” music, like sonatas and symphonies (a so-called symphony is just a sonata for orchestra).

Wm. E. Runyan, © 2015 William E. Runyan

For more insights into the composers and their works you can arrive an hour before each concert for “Words on Music” or read Program Book Annotator Marianne Williams Tobias’ wonderfully informative notes in the program. We are excited to share our time with you in the coming weeks!