Preparing Music: Finding Inspiration

by Theresa Langdon, Viola

Sometimes musicians need to go outside of music for inspiration to do the hard work of learning a piece. I must confess an uncharacteristically rebellious attitude toward learning the twenty-seven page viola part of the Vaughan Williams Fourth Symphony.

I prepared the music as usual, beginning with listening to a recording of the work and hoping it would grow on me. It is angry and sarcastic, two qualities which I try very hard to eliminate from my life. But as a professional orchestra musician, I need to bring my best game to every piece.

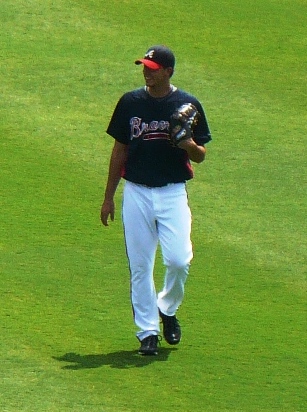

Recently, I was fortunate to read about Atlanta Braves pitcher Charlie Morton, who pitched three innings in the World Series last month. During the second inning, a batted ball hit his leg and broke his fibula. He continued to play, throwing sixteen more pitches, and making three outs. This is the kind of dedication I needed for inspiration to learn the symphony, and it worked.

These past two weeks, which also featured Danny Elfman’s score for The Nightmare Before Christmas and This Midnight Hour by Anne Clyne, could be referred to as the weeks of the diminished arpeggio. Diminished arpeggios are made up entirely of diminished thirds or augmented seconds (e.g. C, E-flat, F-sharp, A, C.) They sound to my ear to be the second-creepiest chord after augmented arpeggios (an augmented arpeggio would be spelled, C E, G-sharp, C). These chords are used by composers to create a sense of dread, mystery, magic, or anxiety. I seriously have played more diminished arpeggios these two weeks than I have in the rest of my career put together! A perfect way to usher in All Hallows Eve.

So, how did I get myself to learn the Vaughan Williams?

After listening to it, I sat down with the part and no instrument and noted the sections that looked difficult. I then played through the whole part lightly, maybe at 60% power. Then I began to work back to front. This is an excellent psychological trick. This way I know I will have gotten to the whole thing!

Vaughan Williams insisted that the Fourth Symphony, written in the 1930’s and considered a monumental work, was not programmatic. During the 1940’s others began to ascribe to it emotions of dismay and alarm at the rise of the Nazis. Here is another possible interpretation, looking back at it from the year 2021. Perhaps you know the eighth string quartet of Shostakovich? Throughout this work written in 1960, Shostakovich is screaming out the acronym for his name: DSCH (D, E-flat, C, B natural). He had been forced to join the communist party, and was fighting for the very existence of his being, personality, and integrity.

Vaughan Williams screams Bach’s name (B-flat, A, C, B natural) during the entirety of this symphony. He may have been fighting for classical form and the symphonic tradition which came down through Haydn and Beethoven in the face of the increasingly aleatoric music (music of randomness) of the 20th century. Given that the form of Vaughan Williams Fourth Symphony is exactly that of Beethoven’s Fifth, could you find this plausible?

At this point, with one performance under my belt, I am finding the Vaughan Williams Fourth Symphony fascinating and worth the trouble. This work may have inspired both Bartok and Shostakovich in their mighty contributions to the vast symphonic repertoire generated in the twentieth century.